|

I’ve been reading MAPS OF THE IMAGINATION: THE WRITER AS CARTOGRAPHER by Peter Turchi, and a statement from that book, which has been on my mind lately — as though it were a message from the (hypothetical) literary cosmos — has resurfaced shamelessly tonight. The chapter of MAPS OF THE IMAGINATION titled “Metaphor: Or, The Map,” begins with an epigraph from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “The writer is an explorer. Every step is an advance into new land.” Turchi elaborates on Emerson's metaphor with an emphasis on the feelings a writer is likely to experience during her/his entry into said new land:

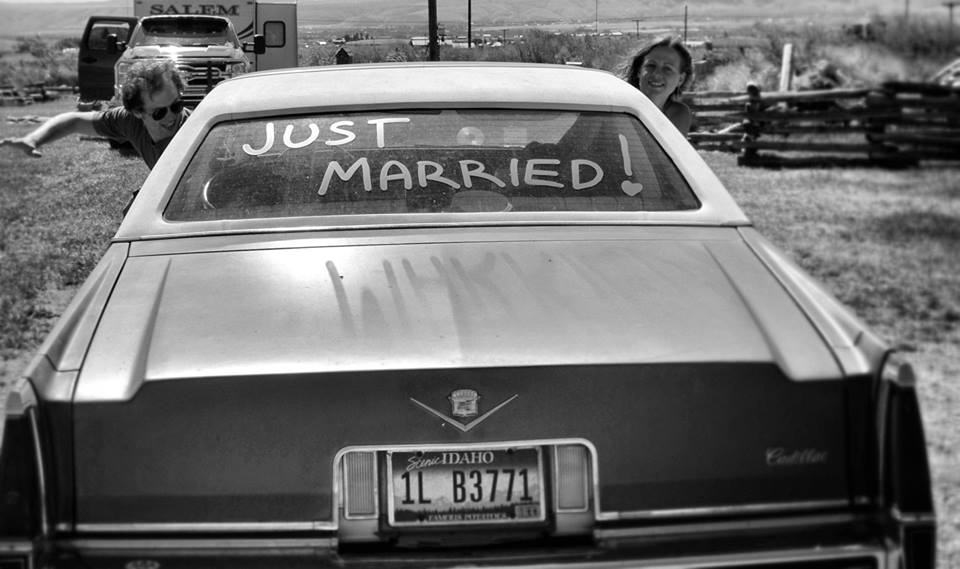

I can’t help but think maybe this is one of the days (if not weeks or months or seasons or, dare I say, years) that Turchi describes. I'd like to say I've stuck to my proverbial guns regarding the file of my memoir that I labeled "NO TURNING BACK." But that would be a lie, and I don't want to tell lies here. I have turned back more than once since I mentioned I had chosen “NO TURNING BACK” as a file label. As for my reason for doing so (for starting at least two new versions of the memoir since then, one of which is labeled "memoir," the other of which I saved so that the file label is first line in the document, which isn't even the first line of that document anymore: "The cat opened its mouth..."), I imagine it's a combination of what's described in the quote above: a bit of anxiety mixed with a bit of despair mixed with more caution than usual, a depletion of boldness, and, of course, as always, the constant risk of failure and its accompanying feeling of being lost (hopelessly) in the realms of what most closely resembles what Turchi notes as limitations of experience and understanding, or what one of my past professors would call a lack of psychic distance. I worked in one of the new files most of the evening prior to coming here. I entered the new land, with a new cigarette, full of excitement. But by the time I'd finished the scene I was working on (and another cigarette), that excitement had reached a desolate plateau. Not only was I unsure of where to go next, I also felt as though this is where I wanted to be instead. Or maybe I had convinced myself that this blog(osphere) might be one of the "discoveries" Turchi says writers sometimes encounter during the course of looking for something else: a thing I can describe as a "success" in relation (however relatively) to what otherwise remains, for now, a failure. Do I merely lack the courage it would take to continue? Am I a fraud? When the pendulum of inspiration swings back the other way (toward "memoir" or "The cat opened its mouth..." or "NO TURNING BACK" again), I’ll probably regret having written this post, and I probably shouldn’t make such confessions (of dead-ends and failures) publicly, but for the moment (presently, as it reverberates), the sentiment remains worthy of note. So it is that I thank the professor who gave me MAPS OF THE IMAGINATION. When she gave me the book, I fear this isn’t exactly where she thought it would lead me — the gift was, after all, meant to commemorate the completion of one of many beginnings of my memoir (what I had drafted of the manuscript by that date served as my MFA thesis, the defense committee for which this professor was a member). Then again, maybe I’m wrong about that. Maybe she knew I would — or that I needed to — go off (of) the grid and thought Turchi would be a valuable travel guide, or, at the very least, a source of consolation for my feelings of artistic waywardness, which have, ultimately, led me here, here being (if not a metaphorical bathtub that belongs to someone else) this blog(osphere), of course, but also the city of Tacoma, Washington, Tacoma itself, in turn, being, at least in relation to any notion of physical belonging (as in home), what this blog(osphere) is to my artistic goals as I've so long understood them: a city in which I never imagined living. More specifically, I write from a long and narrow cement balcony overlooking Stadium Way, which leads to Stadium High School, which is where 10 Things I Hate About You was filmed, and where one of my neighbors is very proud to run (up and down the bleachers) every Saturday. The runner-neighbor — I will call him Fred — is friends with an elderly neighbor of ours, who I will call Ernest and who looks and dresses like Hemingway, thus adding to the charm of the building, more so, anyway, than our upstairs neighbor who fancies WHAM! more than most did in the 1980s and who holds dear a tumbleweed he found in the Nevada desert decades ago while "tripping balls." Deciduous trees line the east side of Stadium Way. Beyond the trees lies Commencement Bay, which is where, in 1841, Charles Wilkes's survey of the Puget Sound commenced. The Northern Pacific Railway chose Commencement Bay as its terminus in 1873 (hence Tacoma's identity as "The City of Destiny"), and its arrival a decade later, coupled with subsequent dredging to provide access to railyards and warehouses, turned Tacoma into a boomtown and improved the Port of Tacoma's status as a hub for trading, the majority of which has continued to take place at said port, which is one of the top ten largest in North America. I'm sure there's a purpose to the row of trees lining Stadium Way — perhaps they help to stabilize the earth beneath the busy thoroughfare — but they block most of my view of the bay and of the port (save for the trio of plumes that rise above them). There are two windows among the trees, however, through which I never tire of watching ships come and go, their frequency a measurement of international industry, their loads importing and exporting an approximate twenty-five-million-dollar's-worth of cars, electronics, toys, grain, forest products, and agricultural products. My husband and I moved to Tacoma from Moscow, Idaho almost two years ago to the date. It seems like more time has passed since we left that blue dot in a red state, which I take as a sign that things have changed for the better during the time we've spent here. Back then, I'd just graduated with an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Idaho and had yet to experience what I have since taken to calling the post-MFA blues (that time, post-graduation, when an MFA-er begins to realize how hard it is to find hope about her/his writing when not so directly and constantly working on it in a supportive environment...a taking stock, if you will, of the reality of her/his so-called achievement and the disillusionment about the nature of that achievement that follows). The winter before our move, my husband had entered the "lottery" to work toward becoming a Longshoreman at the Port of Tacoma. The process to actually become a bona fide Longshoreman, let alone to be "drawn" in this lottery and to then complete the required training is unpredictable and long (and arguably hard), or so we'd heard from my brother-in-law. By then, he had made it to the top of the ladder Longshoremen climb, so there was hope. But I remained skeptical about the prospect of my husband doing the same. Thousands of people had "applied" (or gambled) along with my husband. We'd heard stories through the grapevine (these stories might or might not be true) of women and men hanging their entire futures/fortunes upon the luck of that draw only to be met with disappointment. Near the time of that lottery, a jewelry store in our area was regularly advertising a promotional scheme in which one could buy a piece of jewelry and if it snowed on Christmas Day s/he would get the ring or pendant or whatever for free. The stories we’d heard about hopeful Longshoremen candidates selling their homes or taking other big risks with no guarantee of a favorable outcome didn't seem so different than the stories we’d imagined about women and men buying a diamond ring or pendant or whatever for their loved one from this jewelry story and praying that it would snow on the right day. While my husband and I weren’t banking our future on the prospect of him being drawn in the lottery in question, the fact that his "ticket" was, in fact, drawn was, nonetheless, a bit of a marvel or as good as snow on Christmas Day. Still, it wasn't until he was summoned to report for training that this new career path of his became a reality and and that we decided to leave Moscow for good, a decision that wasn't necessarily an easy one to make. He had a good job in Moscow, and, if we had stayed, I would have had the opportunity to pursue a decent job in editing for a local publication. I was also unsure, even if my husband wasn't, that becoming a Longshoreman was what he should strive to do. When I first met my husband, he wanted to become a lawyer. Later, when we reconnected or reunited (a whole other story) — and, still, when we were living in Moscow, at least up until the opportunity at the Port of Tacoma came knocking and my brother-in-law championed my husband opening the door to it — my husband spoke often of his desire to become a high school English teacher and track coach. Being the aspiring writer I was (and being obsessed as I was with details that seemed like foreshadowing), I saw everything in terms of narrative, and part of me couldn't help but worry that, even after having been drawn in the lottery, my husband's commitment to the pursuit that followed remained a gamble — for even those Longshoremen who are highest in rank cannot predict how much work will be available to them or when. More importantly, I worried my husband would wake up one day and regret his decision not to follow, instead, the philosophical/intellectual and creative path he had been navigating most of his life. I worried that this story in which he was the protagonist, and within which the lottery seemed the inciting incident, would lead to disappointment or thwarted hope. But he had assured me in the past, and he assured me again that spring, that he was a Renaissance man — he wasn't defined by any singular talent or skill but rather was able and willing to pursue whatever opportunity presented and seemed fruitful. My husband is, by nature (and much to my frustration sometimes), humble, I should note, so when he said he is a Renaissance man he was not bragging. Rather, this was a rare glimpse into his vision of his (our) future. In short, I knew I could trust him. Moreover, the kind of physical labor he'd be doing in this career wouldn’t limit his potential to be doing more philosophical/intellectual or creative labor (you can look up the Longshoreman Philosopher Eric Hoffer as an example of a man who managed to do both blue collar work and work of the mind/heart).  "Disappointment is a sort of bankruptcy - the bankruptcy of a soul that expends too much in hope and expectation." Eric Hoffer My and my husband’s honeymoon plans were interrupted by the first summons he received for training at the Port of Tacoma. Rather than being able to set out right away on the road trip we had planned to attend a showing at one of the last drive-in movie theaters within a reasonable distance, we spent the second night of our marriage at his mom and stepdad's house so that he could report to the port that Monday. By the time our honeymoon was over, as was my husband’s training, we were ready for something new. We were excited to relocate across the mountains. We returned to our little apartment in Moscow, the graffiti still on the windows of the Cadillac, packed the place up, and headed back this way — to, for the time being, live with his mom and stepdad, until we were stable enough financially to find our own place. Horace Greeley’s "Go west, young [wo]man" had begun looping in my mind, for better or worse (so to speak), by then, and, that September, as we traveled the 300 miles to Gig Harbor in a 17-foot U-Haul, pulling our 1977 Cadillac named Jack on a trailer behind us, our dog Noodle in her dog bed on top of the carrier we set between us and within which our cat, Big Buns, cried the entire way, it had become a mantra. Greeley's full quote (or one version of it) has been said to be the following: "Washington [as in D.C.] is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country." There is debate about the origins of Greeley’s quote, but for the sake of staying on point I'm not going to get into that now. What I will say, is that the west my husband and I were traveling toward had already been expanded, of course, and that I like to think our U-Haul was free of the "legacy of conquest" historians such as Patricia Nelson Limerick detail about that earlier narrative. Nonetheless, and whether I knew better or not, the positive notion of a land of opportunity was, however, undeniable no matter the era in which we were traveling toward it. That said, I'd studied a great deal of Western history over the course of writing my MFA thesis, the narrative of which was set in the west, so part of me couldn’t also help but scrutinize the narrative we were entering as newlyweds, as though the consequences of this new chapter in our lives were destined to ripple from the less-than-desirable consequences Greeley and his contemporaries — enthusiasts for westward movement and expansion — had had to confront in time. Maybe it was a self-fulfilling prophecy, but, as I’d anticipated (even if I hadn’t wanted to) — and contrary to the original spirit of hope underlying Greeley’s quote and my adoption of it as a mantra — I'd sum up my and my husband’s residence at his mom and stepdad's as a long pause filled with moral lessons from the DVD collection of Little House on the Prairie and a lot of disappointment and uncertainty. Why my husband and I loved/love this TV show (and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books, of course) and why, as almost-thirty-somethings we were watching the show, might or might not be told at a later date. The point for now is that we were unemployed and broke. Not even Petco would hire me, or so I soon learned. So much for the land of opportunity! I sent resumes and applications every morning while watching The Price is Right, and throughout those first few months at least two women with my name, which isn't a common one, were on that show and, as I remember it now, those Sonyas won a lot of loot, if not their showcases. Over time, and cup after cup of Folgers Original, which, to a coffee-lover, is the bottom of the barrel (but also all we could afford...in fact, we didn't even buy it), I began to feel as though the universe was mocking me. My most recent degree, along with the two others I'd earned before it, was in a cardboard box in the garage, and my wedding dress, which my neighbor in Moscow had made and which certain guests at the wedding believed had been imported from Italy, hung above Big Buns's litterbox in the closet of the bedroom where my husband and I slept on a bed his recently divorced brother had recently removed from his recently foreclosed home. This sense of mine that the universe was mocking me became even more acute when my mother-in-law brought a box of tampons (unopened, I should clarify) home for me on my thirtieth birthday. She volunteered at the local food-bank every Thursday and often adopted what wasn't taken by others during her shift, and it just so happened my birthday that year fell on Thursday. Part of what I'd promised to my husband in the vows I'd read to him on our wedding day was to always make the best of what we have, and I was no Harriet Olson, but as I put that box of tampons away — no job, no house to call my own — and despite whatever indigence I am inclined to feel about the amount of money women "must" spend on such products annually and my gratefulness, in turn, for the donation (yet another point to explore at a later date), I couldn't help but wonder how much water such a vow can hold. This is not to say my marriage was threatened by this stage of itinerancy, or that the problems I was facing, as, say, a Sonya who wasn't told to "Come on Down" on The Price is Right, weren't simply First World Problems. I was not, after all, pitching a tent under an overpass or in Seattle's "Jungle" or worse, and the house I was in was warm, and its cupboards were full, its coffee (however generic it might have been) in the pot, the water running. But that didn’t mean I didn’t crave a better outcome or wonder whether it had been a mistake to leave Moscow, whether my husband's prospect at The Port of Tacoma might be one that would never pan out. With little else to do, and lacking the wherewithal to do much at all anyway, I often took Noodle on walks to the end of the road, where, behind a gate adorned with bronze heads of lions, was, despite the unkempt grounds at the entrance, what I imagined must be a mansion. Sometimes, there, while waiting for Noodle to potty, I daydreamed about who might live there, and whether, if they were to see me, they'd be intrigued by my Pacific Northwest attire (rubber boots, Yorkshire Terrier, some thick sweater) and say they were in the market for an over-compensated personal assistant, or, perhaps even better, for a Ghostwriter to help them craft their autobiography about the Life and Times that had led them to their lion-gated, locked-mailbox fortune. Maybe the person who lived there was a Miss Havisham-type who, despite her clocks having stopped and her wedding cake uneaten on the table, had managed to hold on to some wealth, this a fantasy inspired (at least in part, no doubt) by the deflation of my lace dress in the closet that wasn't mine and that hung next to the dress my husband’s grandma, long since relocated to a grave, had worn on her wedding day decades earlier. Even though my husband and I were, meanwhile, trying not to lose hope about the lottery we'd (or he'd) won at the Port of Tacoma, about his potential future as a Longshoreman, and even though I suspected the Miss Havisham I’d been imagining behind the gate at the end of the dead-end road I was living on might only want to hire me in order to live vicariously through me, or, worse, maybe, to "groom" me for the potential loss of a groom, or for the misfortune I didn’t doubt she would predict for me as I stood in the weeds, clasping the iron of her driveway's gate, Noodle at my heels, what remained of my own wedding cake (which I'd never even tasted, in the freezer at my dad's rental, over a mountain range, miles away), doing so was difficult. The Miss Havisham analogy is imperfect, but that doesn't mean the phrase "great expectations" didn't loop in my heart. We'd had so much hope when we'd arrived. Now, when I caught myself spinning my ring around my finger or when my husband, asleep, scooted away from me when I tried to snuggle up to him in bed, I felt as though every gesture the each of us made, and that's not to mention the deflation of our wedding clothes in the closet, was metaphorical. Months passed, and I still couldn't find work. I'm an untapped resource, I began saying to myself and sometimes aloud, but, eventually, only a small fraction of me believed that was the case. Mostly, I reeled from the pangs of the post-MFA blues and found myself wishing I was Caroline or Laura, who had each certainly struggled, but who each also knew much more about survival than I did and who would probably not even know how to begin to relate to the self-doubt I was feeling, but who would, nonetheless, in their selflessness, run miles to "go get Doc Baker" for me, however hopeless such a quest might be. I did not like the shape my story was taking and I wasn't sure how long I'd survive within it. When I had been in a similar predicament, back in 2009, after I’d graduated with a Master's degree in English Literature but had no immediate degree-related career opportunities, I’d started working with my dad. In 2006, having anticipated the burst of the housing bubble, he had quit being a realtor and had begun working with a man who made his living emptying and cleaning foreclosures. My dad, knowing I didn't have any work the summer of 2009, invited me to join him. The work I did with him that summer didn't paid much, and it was, by most accounts, dangerous: there was often broken glass and rusty nails to step on and hazards galore to breathe or to otherwise get too close to. But I enjoyed working with him, and, well, it was work. Plus, I got to see a lot of country. Whatever the dangers of that work, and however poor the pay for it was, it was work I'd eagerly returned to during the summers while I was living in Moscow, pursuing my MFA. The field of foreclosure was there, like a safety net, once again during that fall of my post-MFA blues discontent. Petco might not want me, but the field of foreclosure did. The field of foreclosure did not discriminate, no matter how over- or under-qualified its candidates for employment. Even though he didn’t really want to, for he'd worked in that field in the past, too, and, unlike me, had found it less-than-rewarding, eventually, if only due to my prodding, and maybe, too, his fear of me traveling alone to vacant properties, not to mention crawling under them and walking through the hazards within, my husband joined me. The Port of Tacoma remained something of a wil-o-the-wisp, and at least this way we'd be making some money together. It could be kind of fun, or so I probably tried to convince him. One day I might provide you with a map of where we traveled over the next few months and what I’ve learned about doing 1099s. For now, I will simply say that we put a lot of miles on Jack (the Cadillac), driving to run-down houses and photographing them so that contractors (my dad, for example) could prepare bids for getting them ready for the market and that this often involved navigating suspect terrain. Even though our pay barely exceeded what we spent on the fuel we fed Jack, I can’t say I didn’t continue to love the work we were doing. Call me nostalgic or crazy, but I'd been missing the version of me, who, when working with my dad, had had a front row seat to the aftermath of the Great Recession and its manifestations in the ruin of foreclosed houses. I'd been missing the anticipation of seeing what lied behind each door and of sorting through the wreckage as though each house were a museum or a time capsule. I was (I am) a homebody or a recluse of sorts, mostly, but I'm also something of a dark tourist, or a documentarian who gets a thrill out of the type of adventure that field never ceased to provide. My husband, as I've already indicated, did not love the work, but our partnership was fairly amenable, nonetheless. Mostly, he drove, and I navigated. He kept watch or assisted me as I crawled under houses, or he reminded me to be cautious as I entered those that had been burned or whose walls were decorated by hearty colonies of mold. But once my husband stepped on nail beside a a crappy novel, the only thing that prevented him from breaking the skin being the thickness of the sole of the boot he was wearing (one of a pair he’d gotten for his job as a Longshoreman-to-be), he and I began to argue more frequently over Yahtzee, which was one of the games we often played when we got "home." We argued, namely, about my desire to continue pursuing that field of work (there was a time I was thinking of getting a business license and striking out on my own). Even though that work was the only source of the bacon/bread we were collectively bringing home, he didn't believe it could sustain us, and was, and I can't blame him, deeply concerned about the fact that I wanted to believe it could. It seems the table had turned, in other words: I was the protagonist in the story now, and my husband, the Renaissance man, was the one who didn't want me to wake up one morning regretting a decision I'd made to veer from a "better" course. Ultimately, I gave up on the idea of striking it rich in the field of foreclosure by starting my own business and, instead, rustled up hope to fuel a hunt for a more secure/reliable opportunity for employment. It's worth noting, however, that I gave up that idea mostly because I was overwhelmed by the process/paperwork I would have had to complete to make my own business a reality. Eventually (and thankfully, if only in retrospect), somewhere between a doublewide in Raymond and an RV in Seabeck that might as well have been a cardigan-wearing man’s time capsule, such an opportunity did knock from an IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY my husband's stepdad had been working for and had encouraged me to also apply to. The Miss Havisham I’d imagined owning the mansion at the end of the dead-end road had yet to appear and to offer me employment, so, when the chance to work at said IMPORTANT INSURACE COMPANY came, it was hard for me to decline it. I did apply to said IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, and that company, after the rigamarole of interviews and urine analyses (my first test results came back too clean due to "over-hydration"), ended up hiring me even though Petco, where I would have preferred to be hired, wouldn’t. I continued to let my framed degrees lie in their boxes in the garage at my husband's mom and stepdad's, and, if only for the sake of salvaging what was left of my dignity (as a scholar and a writer), convinced myself that I could not only work in, but that I could thrive in, CORPORATE AMERICA, or that maybe I didn't belong in the academic or the literary world after all but was meant, instead, to transplant those lauds in the expanses of this unexpected context. Leaving the degrees be, I plucked the slacks and the blouses and the skirts and the dresses that, just months earlier, I'd worn as A TEACHER OF ENGLISH AT A UNIVERSITY, from boxes and repurposed them for my new identity as the Future-Something-Important at IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, where, headset attached, I said things like, "I'm sorry about your loss," as in the TOTAL LOSS of a Dodge Charger (owners of those vehicles were among some of the most difficult customers) or the loss of an old Cadillac that had been destroyed by hail in Iowa, or of an SUV that literally caught on fire as the woman on the other end of the line was reporting damage from an earlier accident. "It's on fire. Oh, my God. It's on fire," she screamed, her voice growing more and more distant as she watched flames I couldn't see enveloping her vehicle. Folgers Original in a borrowed travel mug, I commuted daily across The Narrows Bridge to Tacoma with my husband's stepdad, who, like me, had landed his job at IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY after a long spell of unemployment (a whole other story). I felt thankful every morning as I loaded into his Kia, and as he paid the bridge toll and dropped me off, curb-side-service-style, and as I walked the steps up to the revolving, secured door in my teacher-turned-customer service representative-slacks or whatever, my "badge" in hand. It wasn’t long after I started working at IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY that my husband, who was still waiting to reap further benefits from the lottery he’d won months earlier and had since trained to collect (a safety vest and hardhat as proof of his training lying, meanwhile, on a shelf in our bedroom next to our Little House on the Prairie DVD wagon), applied and got a job there as well, a job he needed until he was able to collect a little more from the lottery he had won, which had convinced us to “Go West…” in the first place. It must have been the day he aced his final interview with IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY that we put in applications for rentals in Tacoma and began preparing to move. Newlyweds can only survive so many nights (on a bed, and in a bedroom, that doesn’t belong to them), watching Charles and Caroline struggle, and so many mornings, in turn, watching The Price is Right in a living room they used to only know at Thanksgiving and Christmas. That said, we were hasty, in retrospect, when it came to signing a lease (I had not even seen the place) on the blue, two-bedroom, mini Craftsman, the first rental we had across the bridge. Much to our disappointment, and no matter how hard we tried to convince ourselves that we loved the place, only a couple weeks in that blue mini Craftsman far from any prairie had passed before we couldn’t ignore the plumbing problems. When we learned that the roots of one of the trees in the front yard had intruded the pipes and that there was no reassurance that this would not happen regularly, we started looking on Craigslist again. To make matters somewhat worse, we'd been coveting, meanwhile, or my husband had, anyway, one of the apartments we'd looked at during the time we'd found the mini Craftsman but that we'd ultimately turned down because the mini Craftsman had a yard for Noodle and was, we'd decided, a little cheaper than this other option. I cried when my husband told me, after he'd picked me up from IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, that he just couldn't bear to stay in that house any longer and that whenever he walked by that other apartment building, which he had been doing on his way to and from IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, he felt as though we should have taken it when we'd had the chance. The fact that he was so adamant about his disappointment in our location (that he so openly coveted this other rental) was, however bent I was on not having to move again, something I couldn't shake. The openness of his insistence that we shouldn't stay in that house that I was trying so hard to love was comparable to his insistence that we ought to "Go West," that he really did want to become a Longshoreman. Maybe I cried for the both of us. As luck would have it (or not, depending on how you look at it), the building that held the apartment my husband had been coveting had been sold during the time we'd selected the mini Craftsman as our home. On one of my husband's walks home from IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, after not being able to get ahold of the property manager we'd contacted when we originally toured that apartment, he flagged down a resident who told him the news of the sale and who gave him the contact information for the new owner of the building. He followed the lead diligently, and we began packing once again. The mini Craftsman had been a bust, let's say (we lost our deposit), but we never looked back. When we moved into the penthouse of the historic building we should have moved into in the first place, we were floored: it was a penthouse with a view, an apartment that was within, or just barely...after the change of ownership and the remodels that had been done and the increase in rent that resulted...over our budget! Noodle, too, admired our new view, namely of The Port of Tacoma, from a window in the living room. You should have seen the fireworks that July. We could see all the way to some of the desolate little towns we’d driven to when we were just getting by, photographing foreclosures. We felt very lucky. But by the time our lease was up, that apartment hadn't lived up to the "luxury living" management had advertised when we first moved in (people peed in the ancient elevator, and the property management company didn’t keep their promise for installing state-of-the-art washers and dryers). The view from that penthouse was one we'll probably NEVER experience again (and I miss it to this day), but it wasn't worth the rent we were paying to enjoy it. Plus, my “office” had become an alleyway in which countless cars had been broken into, not excluding, in time, my sister’s car, from which the culprits took some of her most valuable possessions (and on Christmas Eve, as though in mockery of Santa). So it was we returned to Craigslist and soon struck what, despite my misgivings about moving again, seemed like gold. My husband, who rarely ever gets sick, was sick with the flu the day we committed to leaving the penthouse and I found and set up a tour for the apartment we currently call home. I say this because, despite what I've seen first hand in the field of foreclosure, he is much more mindful than I am when it comes to living within our means and because, regardless of whether he regrets it or not, he blames his part of our decision to move here on the fact that he wasn't feeling well. I should, however, clarify that the decision wasn’t irresponsible, whether he had the flu or not. Despite the fact that the square footage here is nearly twice as much as that of the penthouse and despite the fact that this apartment includes the long and narrow cement balcony from which I'm currently writing (and which, with its cover and view of Mt. Rainier and of Commencement Bay is certainly a step up from my “office” in the alleyway), as well as the fact that it has a guest bedroom, a guest bathroom, a secure parking garage, and a dishwasher, it is actually a little less expensive than our penthouse wound up being. It’s true the apartment we’d originally set up an appointment to look at in this building that spring wasn't this particular apartment. The apartment we came here to look at was half the size of this one and half the price. However, when the property management representative/tour guide asked us if we wanted to see other options, neither of us said no. So we looked at the next level up (in terms of amenities and price), and when our guide asked us if we wanted to see the “deluxe” apartment neither of us said no. Whatever the case might be — whether it’s because my husband had the flu that day or because we really wanted a second bedroom and bathroom and/or didn’t want to live on the street level -- when we walked into this apartment, there was little question that we felt as though we’d finally arrived home. The building was built in 1951 with architectural prowess (it is quite unique compared to the buildings surrounding it). The units are terraced, but you wouldn't notice they are, except by passing the building on Stadium Way or while descending or summiting its parallel street, which is a steep incline upon which at least every tenth vehicle bottoms out, scraping its front bumper or undercarriage. The interior of the apartment maintains much of its original charm, including built-in shelving and closets and built-in table (nook) and drop-down ironing board (which we'll probably never use) in the kitchen. We also have a fireplace, but we haven't quite learned how to use it. Once, last spring, it filled the whole apartment with smoke and set off all the fire alarms, and I’ve since heard evidence of birds nesting in it. I'd quit my job at IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY a few months before we moved into this apartment (I'd been offered a teaching gig — finally, I was no longer an untapped resource!), but my husband was still working there, looking longingly at The Port of Tacoma through the trees on Stadium Way whenever he was out on the balcony. As though to spite us, The Port of Tacoma interrupted our 2nd anniversary when my husband received another summons. This time, however, the summons was more of a "promotion," in that it was an invitation of sorts to begin working there on a more regular basis. In the beginning, he was an "Unidentified Casual." Now, he had become a "Casual" (identified). That he contemplated giving up becoming the 21st Century Eric Hoffer in order to continue sitting at a desk in a cubicle at IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY, where he was treated extremely poorly in relation to what he contributed and where he dealt with disgruntled owners of Dodge Chargers, is laughable to us now, but it wasn't at the time, for, not only did this VERY IMPORTANT INSURANCE COMPANY cast a spell over its employees, a kind of CORPORATE WORLD KOOL-AID (even though every day I woke up and knew I had to walk down the Spanish Steps to that building I felt like I might die, or as though I was dead already, I, too, contemplated staying when I'd been offered an opportunity to return to the Ivory Tower), relying on the security of his Longshoreman work at The Port of Tacoma still was (and it remains) something of a gamble. Ultimately, however, we have experienced a happy ending to the first three years of our life together as a married couple, and my husband's pursuit of a career as a Longshoreman has played a significant role in that outcome. The rest is, as they say, history: after having dragged our belongings around so many times since we left Moscow, we've settled for a while here. But while this (Tacoma, my apartment, its balcony, this state of denouement) is where I'm writing from in the present, and while I've been writing this post in the present tense so far, you should keep in mind, if only as a disclaimer as to why the post is so long-winded and perhaps not as coherent as it could be, that I began drafting it almost a year ago. I was writing more regularly then because I was on summer break from teaching and otherwise unemployed. I'd developed a routine, especially when my husband was working nights, a routine that felt very romantic, in the sense that I was a kind of night-owl-writer and wife of a Longshoreman, and not one who complained when her husband was away. I'd work on my memoir until I reached a dead-end or wanted to give up on it altogether, and then turn to this website, this blog, as a place where I could process my memoir-related struggles, or to just feel as though I was still being a writer in some capacity, even if I wasn't being a writer in the way I preferred to be. That particular night, my husband was lashing down cargo containers, or securing them to a big ship bound for someplace neither of us knew — Japan or China, likely. Back then, he’d tell me he never knows what's on a ship unless it was cars (Kias, most frequently), in which case he’d disembark swiftly, but safely, within them and park them not far from where the ship they’d arrived on had docked, adding mile five or six or maybe ten or fifteen to their otherwise virgin odometers. Though it's been some time, tonight is no different — not really — and there is comfort in that. I'm on the same balcony I was on when I started drafting this, and my husband is, at this very moment, working on a car ship. He texted me when he got the job, as he always does now. He told me what he would be doing tonight in a short hand he's developed: Working. Car ship. Love! I responded the way I always respond now: Okay! Be safe! [lipstick kiss emoji, lipstick kiss emoji, lipstick kiss emoji]. Now, I sometimes add a series of emojis alternating between the anchor and the strong arm, or, if he's doing something with a train or a tractor, its respective emoji, alternating with the anchor and/or the strong arm. But I am digressing again. Here's an image to begin to end on: Last summer, when I first began writing this, our upstairs neighbor’s prize tumbleweed had been the first of many “gifts” that have since fallen from his balcony to ours. My husband, when he’d gotten home from a job “on the docks” asked me if the tumbleweed was something I'd found and brought home, which was somewhat insulting. I'm a collector, sure, but not of tumbleweeds. Our neighbor told the story about the tumbleweed — how he’d found it in the Nevada desert while he was on acid — when he came to collect it the morning after it had fallen onto our balcony. Upon his departure, he wound up forgetting his flip-flops on our doormat, which is where they remained for a few days before he realized he'd walked off barefoot. There's charm in that neighbor, too, just as there is in Ernest’s white pants, white blazer, captain’s hat, and white Ford Taurus. Plus, recently, he's switched from WHAM!'s "Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go," to Bob Marley's Greatest Hits (or from cocaine to weed, depending on how you want to look at it, and/or how you judge a person by their soundtrack(s)). This is to say, perhaps, that our apartment is a delightful place to live, if a bit strange. I wrote a short poem, when we first moved here and I set up my "office" on the balcony with table of reclaimed wood my brother-in-law made. The poem is about the elderly couple that lives in the apartment below (and to the right) of this balcony. We can see through their kitchen window, and they have a green recliner identical to one in our living room, and a TV tray that looks one I often use as a mobile desk when I’m traveling. The poem imagines that their kitchen window as a portal to the future, that, really, that man and woman are my husband and me, years from now, and that maybe they never looked directly at us because they didn’t want to mess with the time-space continuum, or because the us here in the present don’t actually exist to the version of us we can see through that window. I don't know. It seemed very insightful at the time and represents a sense of satisfaction, like I am where I belong. I call this apartment Shangri-La when I'm not calling it Trashout Barbie's Dream Apartment. The latter is a nickname that harkens back to my friends and I deciding our "Barbie" names during one of the summers when I still lived in Moscow and was working off and on with my dad in the field of foreclosure, "trashout" being shorthand for emptying a foreclosure. My friends told me over wine after I’d returned from a trashout route that if we reimagined a child’s Barbie collection to reflect the zeitgeist of the economic recession, and if I was part of that collection, I would be called Trashout Barbie, the increasingly eclectic assortment of things I’d salvaged from homes of strangers my accessories, which had been acquired (rather than sold) separately. I can’t remember why Barbie had been a topic of conversation that night — maybe I’d found her in a child’s bedroom or maybe I’d been talking about my and my sister’s Barbie’s Dream Home, which was a featured Christmas gift in a VHS home video my parents recorded the year before they divorced (a video I’d been obsessing over and writing about) — and I must say Barbie and I have little, if anything, in common. But the profane anti-Barbie-ness of the analogy delighted me, nonetheless, and the nickname stuck, eventually following me to my/Trashout Barbie's "trashout wedding" (my and my husband's wedding was decorated with castoffs from foreclosures, including the typewriters that adorned the picnic tables where our guests ate, including the picnic tables themselves) and here, to this apartment in this city where I never thought I'd live. Once, my dad salvaged a bed from a foreclosure (my husband and I needed a new one but couldn't afford to buy one and the bed my dad had found was in "mint condition"), and it is upon that very bed, which my dad delivered to this apartment over the winter, despite his bout with cancer (which is yet a whole other story), that my husband and currently sleep. I don't know what my bed or the delivery of it and these snapshots of my neighbors have to do with the heart of the matter (which is, I suppose, my struggles as a writer), but here I am, trying to wrap this up, this series of digressions about how I arrived in this city (and here in this blog(osphere)), and on the balcony of this apartment, this state of mind I'm loitering in as I peer through the trees at what I can see of where my husband is tonight and through the window of the apartment where future-me and my future-husband are turning off our lights after having eaten our nightly bowls of Cheerios. Otis Redding's "Sittin' on the Dock of the Bay" or Bon Jovi's "Living on a Prayer" would be a better soundtrack to this backdrop than WHAM! or Bob Marley's Greatest Hits, but I haven't yet committed to a soundtrack war with the neighbor upstairs, and part of me finds his selections endearing. He's in his late forties, he owns a shop of tea, and he confesses that he sometimes drinks too much and, to the detriment of Ernest’s peace and quiet and my own (and my husband's) loses track of time, and of volume — no pun intended — and I can empathize with that. He might not be exactly where he thought he'd be in life by now. But, even though I'm happy where I am, neither am I. Here's another image: I'm sixteen, and I'm driving my 1980 Honda Accord hatchback, The Silver Bullet, I called it, to Tacoma, to my friend's aunt's house, smoking a rolled Bugler cigarette. This is before cell phones and GPS, and I'm lost. I exit (maybe because I'm lost — I don't remember), and, suddenly, I'm in some desolate industrial region of the city, all alone, and it feels like the moment on Adventures in Babysitting (except I'm by myself) when Elizabeth Shoe gets a flat outside of suburbia and a trucker with a hook for an arm pulls up. Looking back, and having driven around the Port of Tacoma since then, I wonder if it wasn't there I exited. Wherever I stopped, and regardless of the circumstances, that was, for a long time, what I thought about Tacoma, or how I saw myself in it: a girl, vulnerable, lost. Nothing bad happened that particular night — eventually, I reoriented, and got to my destination — but that didn't eliminate the negative association I had about this city, and that negative association wasn't the only one I had when I thought about it. D.A.R.E: To Keep Kids Off Drugs also comes to mind when I think of my past impression of Tacoma. Tacoma was, in my adolescent mind, a hub for drugs and gangs and crime, D.A.R.E a warning against drugs, primarily, but also a means to warn against all of the above. To make a story that could be longer shorter, when I was driving through this city at the age of sixteen, at the speed of 60 miles per hour, had you been a passenger of mine and told sixteen-year-old-me with her hippy bandanas and rolled cigarettes and torn Levi's 501 jeans that I'd live here one day, I wouldn't have asked what you were smoking while turning up the mix tape in my Blaupunkt stereo. That's not to say that I have ever had a strong idea of where I'd "end up" — in fact, as I think about it now, I'm not sure that was a question to which, circa my ownership of The Silver Bullet (of which I have no photos, unfortunately...I just tore apart the spare bedroom, looking for one) I had an even remotely definitive answer, except that it wouldn't be Tacoma. But one's sixteen-year-old-self can accurately hypothesize only so much about the trajectory of her life, even while behind the wheel, stick shift in hand, "Cecilia" blaring. Tonight, Mt. Rainier looms from an airplane in which passengers are arriving or departing from SeaTac Airport, and — when it isn't night or overcast — I can see it nearly as clearly from here, just from a different vantage: a constant reminder of how small I am, of how inconsequential, yet significant, the decisions I've made about the course of my life have proven, or will prove, to be. Welcome to....

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

S.J. DunningWriter, editor, SAHM of three, infertility advocate, pregnancy loss advocate, ex-ballerina, nostalgic, record-keeper, documentarian Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed